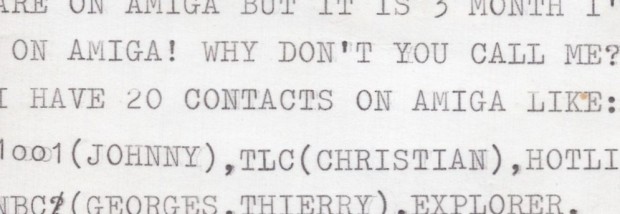

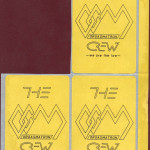

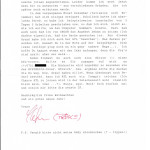

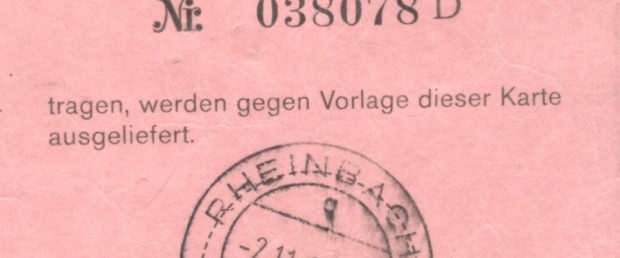

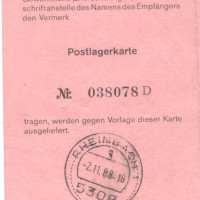

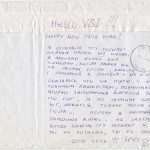

Bodo/Rabenauge provided us with this scan. It’s an inconspicuous pink paper slip, slightly bigger than a credit card. For German crackers and demosceners in the 1980s, however, it was the single most important tool for long-distance communication and data transfer, before the introduction of BBS‘s and a long time before the Internet.

PLK is short for “Postlagerkarte” and roughly translates as “Mail storage card”. Introduced by the German Imperial Post in 1910, it was a service that enabled customers to receive mail anonymously. The pink slip was the only ID you needed at the post office counter to pick up the mail sent to the particular PLK number. Also, unlike P.O. boxes (“Postfächer”), you could get a PLK for free and without having to reveal your identity. From the mid-1980s onwards, when German law enforcement began to take piracy more seriously, PLKs became the preferred software exchange channel for computer kids – and particularly for their “elite” segment, the crackers and swappers, who raised illicit software exchange to a semi-professional level. Going to the post office and picking up the latest disk-filled envelopes was part of the most active sceners’ daily routine. Some even went as far as having multiple PLKs across their hometown.

Of course the German public, and particularly the law enforcement authorities, became aware of the scheme rather quickly. Already in 1984, some computer magazines stopped publishing classified ads with a PLK contact address, as it began to have an air of piracy and fraud around it. In 1986, the infamous copyright lawyer Günter von Gravenreuth described the PLK principle to a specialist audience. To cope with the PLKs’ anonymity, the authorities had to go to great lengths. After finding out which post office a particular PLK was assigned to, the police had to place plain clothes officers at the post office and wait until someone showed up to collect their mail. 1980s cracker magazines are full of reports about people getting “busted” in this manner. Jeff Smart, editor of the papermag ‘Illegal’, described the typical situation in 1988: “Normally you get a PLK […] without giving your name or address, so the cops have to wait in the post office until you appear and get your packages from the counter clerk. Then they politely ask you: ‘are you really in that group X.X.X. ???’ and GA-BOSH! Game over for you!“. Such confrontations at the post office, which sometimes escalated into spectacular chasing scenes, could also lead to a house search.

Those who used PLKs for swapping resorted to different strategies to counter these measures. After the dangers of picking up PLK mail became common knowledge, sceners went to the post office in groups: “One of us took a peek, and if the situation seemed safe, he beckoned the rest of us.” Those operating on a more professional level resorted to hiring younger kids who would pick up their mail for pocket money. These, ideally, did not even own home computers, and thus were perfectly “clean” when apprehended by the police. Other groups began leasing P.O. boxes in neighbouring countries with a more lax attitude towards piracy, such as Belgium or Luxembourg, and periodically drove over the border to pick up their packages.

All in all, PLKs quickly turned out to be anything but the universal remedy for those involved in software swapping. However, they were still widely used – most importantly because they allowed the hiding of real names and addresses not only from the police, but also from other sceners. Thus, PLKs also became the preferred method of data exchange for demosceners – some of whom even wrote to commercial computer magazines arguing that having a PLK did not always imply criminal intent. The notion of a PLK as a synonym for a contact address within the scene became so popular that even in a Yugoslavian crack intro, the group introduced their contact details (an ordinary street address) as “our PLK”. Thus, the concept of a PLK gained international cultural significance within early home computer culture even beyond its original meaning.

The German Post abolished the PLK system on 1 June 1991. The scene did not shed many tears over it – after all, much of the data exchange was already relocated onto BBSs. However, a significant cultural practice disappeared, to be forgotten by all except by those who experienced it themselves.

Gleb J. Albert

Got a personal PLK story to tell, and want to share it with our readers? Please do get in contact!

PS: The scan of Bodo’s PLK is available here.